Andyʼs working notes

About these notesSpacing effect

You’ll remember material more reliably if you study it on separate occasions, with some space in between—rather than if you spend the same amount of time cramming it all in one evening.

To put this another way, successive reinforcements flatten the Forgetting curve, so you can wait longer and longer between each review. Well-timed spacings flatten that curve to a greater degree.

Spaced repetition memory system algorithms taken advantage of this to implement efficient learning systems.

Optimal spacing

The intersession intervals shouldn’t be increased without bound, since that decreases the likelihood that you’ll remember the material when reviewing, which in turn diminishes the reinforcement effect on your memory. The optimal ISI depends on the retention interval (RI)—the time between the final study session and the test.

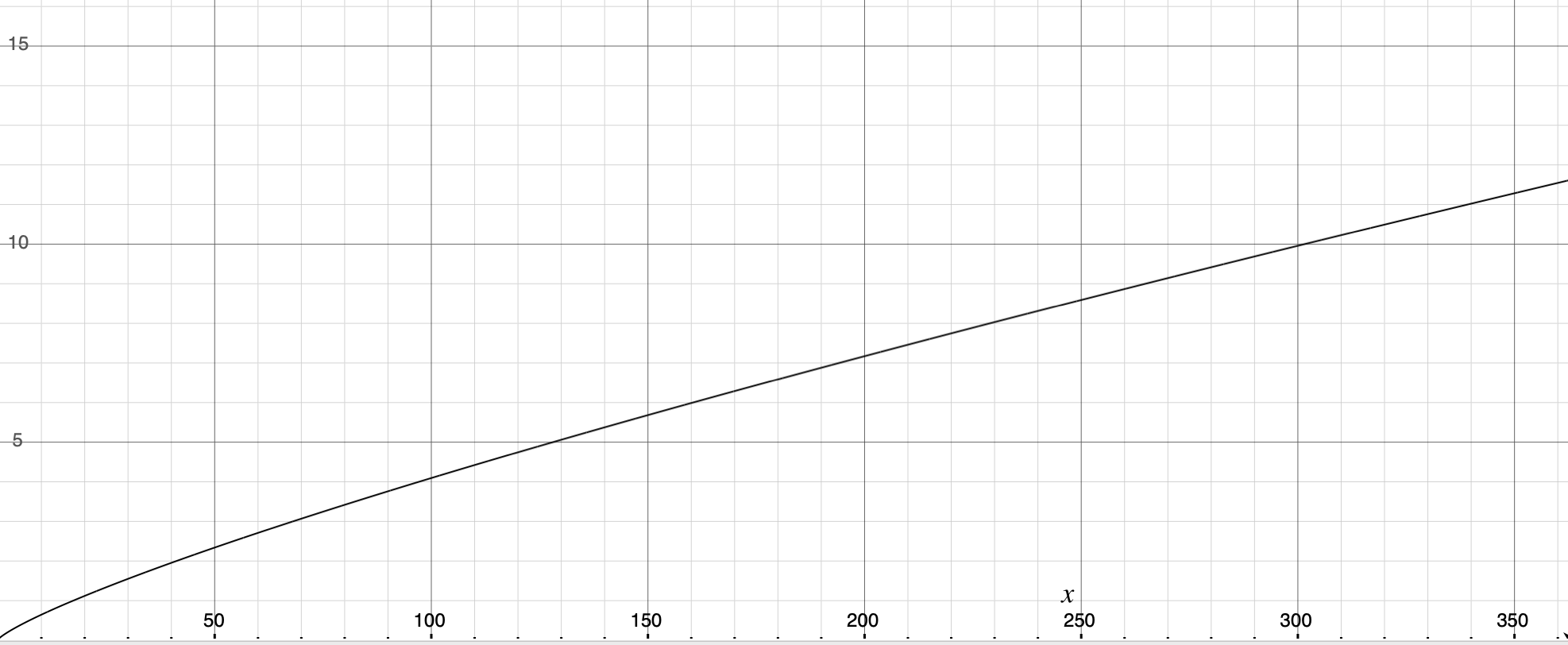

Mozer and Lindsey (2016) derive this power-law relationship for individual study sessions from various empirical data sets:

Optimal ISI = 0.097 * RI^0.812

Which has this shape:

It looks roughly linear to me, honestly. Their data sets don’t include anything outside of a 1 year RI, so we shouldn’t trust the function beyond this range.

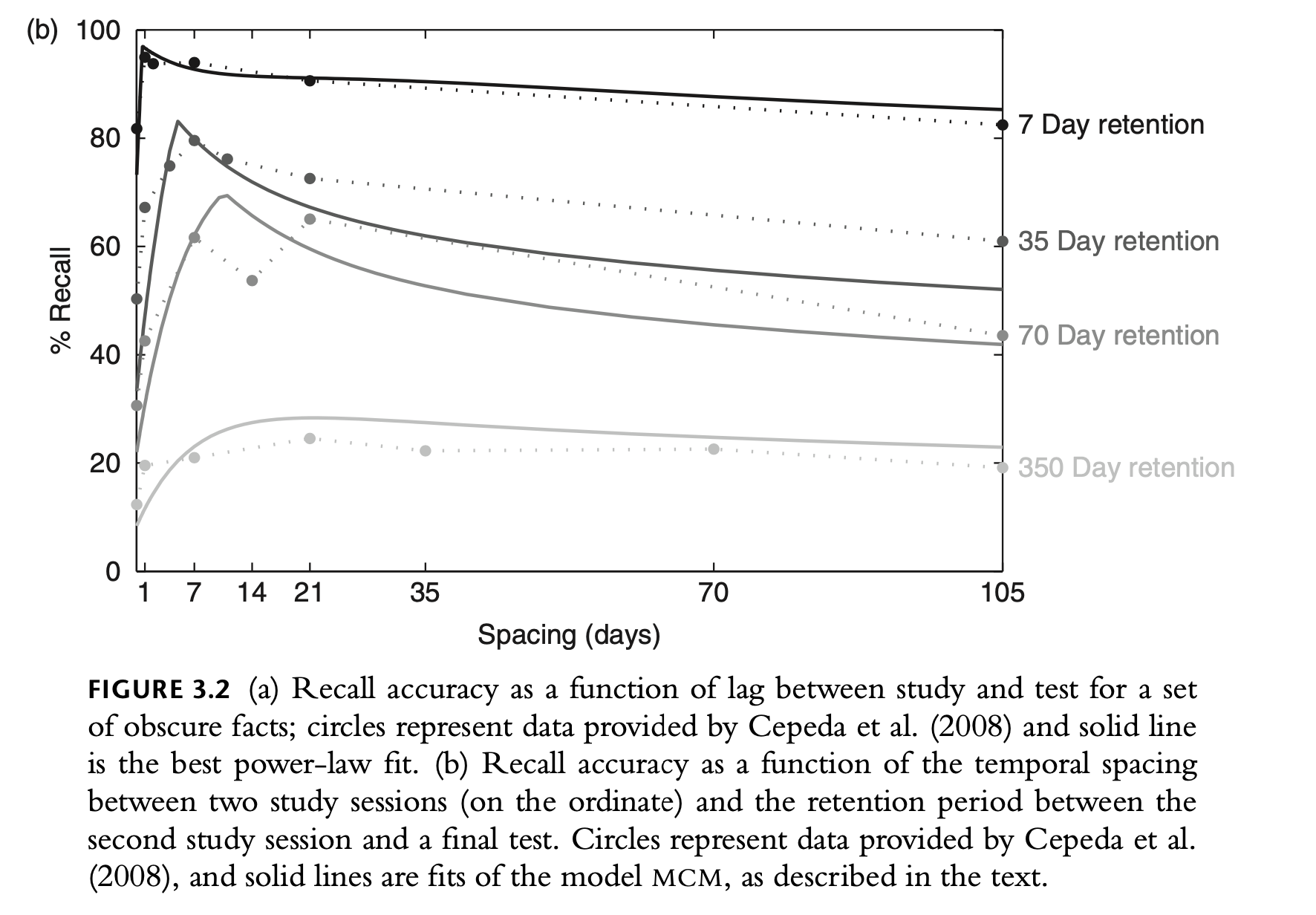

Also, this function doesn’t seem to fit Cepeda et al 2008’s data very well:

e.g. they found that OISI ~= 5 for RI = 35, but the power law fit finds OISI = 1.8, which empirically performed much worse in that study.

Collected empirical evidence

Kornel (2009), in an experiment involving GRE-type vocabulary:

Combining the three experiments, 90% of participants learned more in the spaced conditions than the massed conditions, whereas only 6% of participants showed the reverse pattern.

Possible explanatory theories for the spacing effect

- “Encoding variability”: spacing varies the context, which leads to richer, more diverse encodings representing those contexts

- Spacing demands less concentrated effort and focus than massed study.

- Less accessible memories are more reinforced by retrieval, which may enhance learning via Two-component model of memory

- “Predictive-utility”: if an item is typically retrieved on a short interval, your mind assumes it’s no longer needed after that interval elapses; longer intervals establish longer periods of need.

Q. What term is used in spacing effect studies to refer to the time between sessions?

A. Intersession interval (ISI)

Q. What does ISI stand for in spacing effect papers?

A. Intersession interval.

Q. What term is used in spacing effect studies to refer to the time between the final study session and the test?

A. Retention interval (RI)

Q. Distinguish “intersession interval” and “retention interval” in spacing effect studies.

A. The former refers to time between study sessions and the latter to the time between the last study session and the test.

Q. What’s the “spacing function” refer to in spacing effect literature?

A. Recall accuracy as a function of intersession interval

Q. What’s the characteristic shape of the spacing function?

A. A hill: a relatively sharp initial increase in accuracy followed by a slow decline.

Q. What’s the “optimal ISI” refer to relative to the spacing effect?

A. The peak of the spacing function: the ISI which produces the highest recall accuracy.

Q. The optimal ISI depends strongly on what other interval?

A. The retention interval (Cepeda et al, 2006; via Mozer et al, 2009)

Q. What’s the central claim of encoding variability theories for the spacing effect?

A. Spacing produces better recall because it encodes memory traces with a wider variety of psychological contexts, providing more opportunities for overlap with recall contexts.

Q. Why would having memory traces involving a wider variety of psychological contexts lead to more reliable recall?

A. Encoding specificity principle

Q. In encoding variability theory, why not increase the ISI without bound to get maximum context variability?

A. As ISI increases, retrieval becomes lossier because each study context overlaps less with the next.

Q. What’s the central claim of predictive utility theories for the spacing effect?

A. The mind “learns” how long memories are needed according to their access patterns; longer study intervals encourage longer storage.

References

Branwen, G. (2009). Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning. Retrieved December 16, 2019, from https://www.gwern.net/Spaced-repetition

Kornell, N. (2009). Optimising learning using flashcards: Spacing is more effective than cramming. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(9), 1297–1317. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1537