Andyʼs working notes

About these notesCOGS 101B - Lecture 11 - Knowledge shapes perception continued, attention

Face recognition

(see Human perception: face recognition)

Attention

“Everyone knows what attention is. It is taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. … It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.” — William James

Attention allows us to {select and enhance} {relevant} perceptual information.

{Selective attention}: attending to one thing while ignoring others.

In a {dichotic listening task}, subjects {hear a different message in each ear}. If they’re asked to repeat one of them back, they’ll miss high-level information ({meaning, syntax, language changes}) in the unattended ear, noticing only low-level information ({odd noises, gender switches, strange voices}).

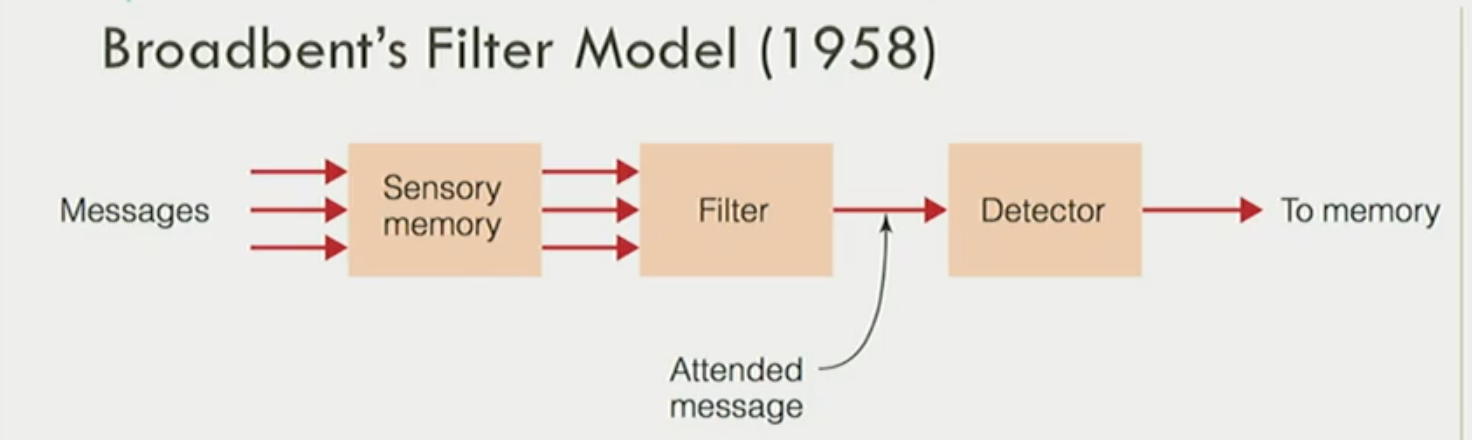

The experimenter, Broadbent, proposed a bottleneck model for information processing in selective attention. This model provided testable predictions for selective attention. Some problems emerged: people could recognize their own name in the unattended ear (Moray 1959), and people combine words from the unattended ear to make a more coherent sentence (Gray and Wederburn, 1960).

Q. What’s an example of a word a participant in a dichotic listening task would notice if spoken in the unattended ear?

A. Their name.

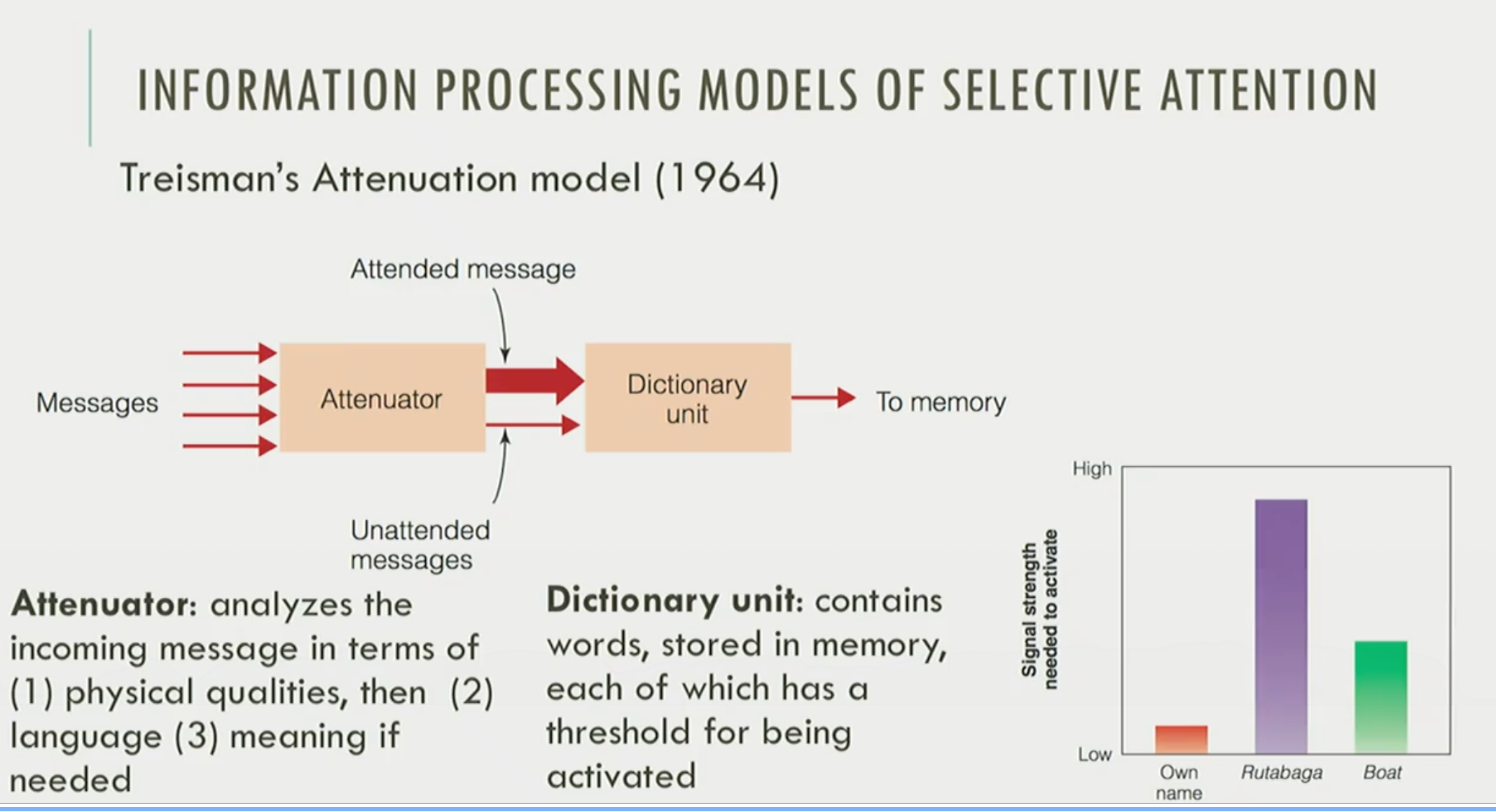

Treisman tried to improve upon the filter model with an Attenuation model (1964), in which the unattended messages still pass through, but with lower emphasis. A “dictionary unit” contains words which can be activated at a particular threshold. Your own name might require only a very low threshold, so the “quiet” signal from the unattended message would still activate it.

The filter and attenuation models are “{early}” selection models: the filter’s positioned early in the process, so that {most sensory input in the unattended ear is not processed for meaning}.

Alternate “late” selection models suggest that all the information’s mostly processed, but the unattended info doesn’t make it to working memory. There is some evidence for late selection: e.g. words in the unattended message will influence your interpretation of the attended message (“they were throwing rocks at the bank” and “money” produces a fiscal interpretation, rather than a river)

Q. How do “late” selection models interpret selective attention?

A. All information is processed, but only some makes it to working memory.

Q. What’s an example of evidence in support of “late” selection models?

A. Words in an unattended message influence the interpretation of an attended message.