Andyʼs working notes

About these notesKarpicke, J. D., & Zaromb, F. M. (2010). Retrieval mode distinguishes the testing effect from the generation effect. Journal of Memory and Language, 62(3), 227–239

Are the Testing effect and the Generation effect simply the same thing? They’re often equated, and indeed, I’d equated them in my own notes. This paper describes a series of experiments which attempt to demonstrate that a different underlying mechanism drives the two phenomena, and that retrieval practice has a greater impact on memory than generation.

A broad outline of the experiments:

Subjects were first exposed to a list of target words. Then the subjects were shown the targets again intact for Read trials or they were shown fragments of the targets. Subjects in Generate conditions were told to complete the fragments with the first word that came to mind while subjects in Recall conditions were told to use the fragments as retrieval cues to recall words that occurred in the first part of the experiment. The instruction manipulated retrieval mode—the Recall condition involved intentional retrieval while the Generate condition involved incidental retrieval. On a subsequent test of free recall or recognition, initial recall produced better retention than initial generation. Both generation and retrieval practice disrupted retention of order information, but retrieval enhanced retention of item-specific information to a greater extent than generation.

The conclusion:

There is a distinction between the testing effect and the generation effect and the distinction originates from retrieval mode. Intentional retrieval produces greater subsequent retention than generating targets under incidental retrieval instructions.

An interesting bit of background review on the generation effect, which suggests it may not actually be as powerful on its own as suggested:

Thus there is often no difference in free recall of read vs. generated lists, and in fact sometimes there is an advantage of reading over generating (e.g. Nairne et al., 1991; Schmidt & Cherry, 1989). The enhanced item processing that occurs in a pure list of generated items is not sufficient to counteract disrupted order processing and produce an advantage in free recall relative to a pure list of read items.

In their first experiment, students were shown a list of words. Then they were asked to complete a word pair including a fragment of a target word (e.g. heart – l?v?). One group of students was asked to recall the target word from memory; the other was asked to generate it. Then students were asked to recall as many words as they could. Students who studied with the instruction to attempt to recall word targets performed substantially better than the other conditions; students who studied with instructions to generate the word targets performed no better than those who simply read the targets. That is: there was a testing effect but no generation effect.

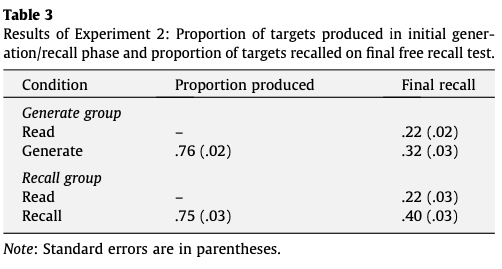

The second experiment explored the “order processing” theory suggested earlier by presenting a “mixed list” of stimuli: is the order of words being remembered? Or is it the items themselves? Does retrieval practice disrupt order processing, as has been suggested by some prior trials? The design of the second experiment was the same as the first, except that in the second phase, half of the word pairs were shown intact, with no generation or recall. This experiment produced both a generation effect and a testing effect, with the latter somewhat stronger than the former.

The items which were simply read performed similarly in both conditions, suggesting that retrieval practice doesn’t work by improved recall of order information: it enhances item-specific retrieval.

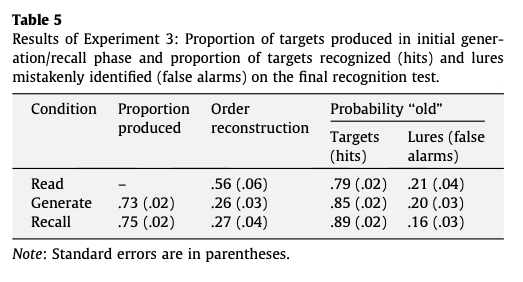

The authors ran a third experiment akin to the first but replacing the third phase’s free recall with a recognition test and adding a reconstruction of order test. Order reconstruction was far better when neither generation nor recall was in play; the latter two conditions had similar accuracies. By contrast, in the final recognition tests both generation and retrieval improved recall (with a non-significant advantage to the latter).

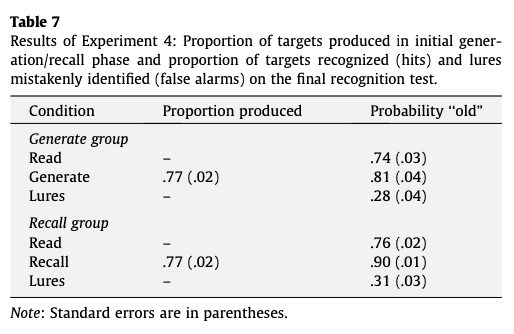

A fourth experiment applied the third’s modifications to the mixed-list design of the second. This experiment produced effects in both cases again, with retrieval practice producing significantly better recognition performance.

The conclusion from this research is that when subjects are in an episodic re- trieval mode (Tulving, 1983), consciously attempting to reconstruct the past enhances future retention more than generating knowledge under incidental retrieval condi- tions and this advantage stems from enhanced item-spe- cific processing evoked by intentional retrieval.